Blue Chip Issue 80

- Text

- Fintech

- Technology

- Dfm

- Equity

- Management

- Schroders

- Advisers

- Planning

- Financialservices

- Momentum

- Asset

- Wealth

- Investing

- Portfolio

- Global

- Advisors

- Infrastructure

- Funds

- Retirement

RETIREMENT How the

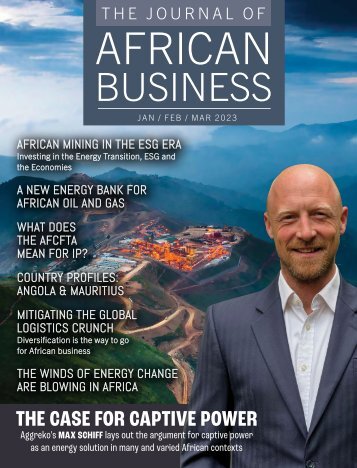

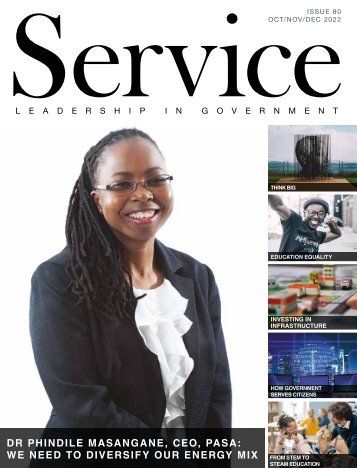

RETIREMENT How the Fourth Industrial Revolution is creating the need for new solutions Making sense of today's retirement landscape. Part 1 T wo great socio-economic metamorphoses are converging at a historically unprecedented pace. They are colliding with doggedly persistent contradictions in long-term savings behaviour. It is a recipe for crisis. But also, for opportunity. In this, the first of a four-part miniseries exploring the rapid evolution of an age-old conundrum, we delve into the digital disruption of work. And why it is contributing to an urgent need for a paradigm shift when it comes to planning for financial freedom. “We stand on the brink of a technological revolution that will fundamentally alter the way we live, work and relate to one another.” Klaus Schwab, 2015

RETIREMENT Technology is completely changing the workplace “We stand on the brink of a technological revolution that will fundamentally alter the way we live, work and relate to one another,” wrote Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum (WEF), in December 2015. “In its scale, scope and complexity, the transformation will be unlike anything humankind has experienced before.” Schwab’s proclamation arrived at the transition into what many now consider to be a new age in man’s relationship with machines. He has been credited with introducing the concept of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, a continuation of the third, digital revolution; defined by the ongoing automation of work; characterised by a confluence of new, smart technologies; and distinct in its exponential, rather than linear, pace of development. Schwab’s idea built on a long tradition of preceding evidence and thinking, such as seminal research carried out by Oxford researchers Carl Frey and Michael Osborne, who, in 2013, estimated that nearly half of all jobs in the US were at risk due to computerisation. Frey and Osborne’s research, meanwhile, had been motivated by a prediction made by British economist John Maynard Keynes in his 1930 essay Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren. In the half decade since, intensifying research into business’ rapid adoption of artificial intelligence and off-balance sheet talent has popularised the field of enquiry known as the Future of Work. The burning question at its centre: What jobs will machines replace, and what jobs will they create? It was a profoundly important question, in 2019. There was a decade’s worth of change, in a year Today’s emerging thinking is that the global Covid-19 pandemic has had the effect of leaping many aspects of the digital transformation forward along its inevitable trajectory, in some areas by a full decade. Business’ digital inertia has been dissolved by crisis. Consequently, “In addition to the current disruption from the pandemic-induced lockdowns and economic contraction, technological adoption by companies will transform tasks, jobs and skills by 2025,” reads the WEF’s 2020 Future of Jobs report. While the Fourth Industrial Revolution, combined with a shift in market forces, is “creating demand for millions of new jobs, with vast new opportunities for fulfilling people potential and aspirations,” it also poses the threat of intensified “job displacement and widening income inequality”. The WEF now estimates that, in just five years, 85-million jobs may be displaced by a shift in the division of labour between humans and machines, which sounds daunting. Yet it also estimates that 97-million new roles, where people have a “competitive advantage” over computers, will be created. While Frey and Osborne estimated that nearly half of all jobs in the US are at risk, executives surveyed by the WEF estimate that half of all employees will need to be reskilled in the coming few years. At a global level, the situation is not one of pure and widespread “technological unemployment,” as cautioned by Keynes. Instead, we may well be in the grips of what he termed, “the growing pains of over-rapid changes, from the painfulness of readjustment between one economic period and another,” as the world, once again, transitions between industrial eras. All of this has a profound effect on retirement savings Whatever the future holds, there is one unambiguous lesson we need to learn from the current workplace transformation: the skills we have today may not be relevant tomorrow. A mindset of constant learning and personal evolution is becoming very necessary to keep up with the times. When it comes to planning for financial freedom, this is incredibly relevant. Intuitively, most people know that they need to save for their futures. This, one might say, is intergenerational knowledge. We learn from our elders who have achieved financial freedom in retirement, and we learn from our elders who, sadly, have not. But what many of us do not know is that we can no longer rely on a given set of skills to provide a consistent income into the foreseeable future. We have miss-learned from our elders who spent their lives at work in a given role. This can be referred to as the intergenerational fallacy. It is a well-documented reality that the majority of South Africans do not save enough from their incomes to achieve financial freedom in retirement. When this intersects with the new reality where it is becoming increasingly uncertain whether the skills that enable those incomes will remain relevant, we have an age-old problem, colliding with a rapid evolution. The truth is that the retirement savings industry failed to solve the problem of inadequate retirement provisioning, before the Fourth Industrial Revolution. We need a new solution. In the next article in this series, we look at how increases in longevity are affecting retirement planning. Kenny Rabson, CEO of Discovery Invest “In its scale, scope and complexity, the transformation will be unlike anything humankind has experienced before.” www.bluechipdigital.co.za 21

- Page 1: Issue 80 • Jul/Aug/Sep 2021 www.b

- Page 7 and 8: Safe and easy. Life or Investment p

- Page 9 and 10: Not all group risk solutions are cr

- Page 11 and 12: A body such as ours needs all the v

- Page 13 and 14: On the money Making waves this quar

- Page 15 and 16: Momentum Financial Planning recruit

- Page 17 and 18: TECHNOLOGY The future of investing

- Page 19 and 20: To illustrate how OUTvest can strea

- Page 21: INFRASTRUCTURE There are currently

- Page 25 and 26: THE BALANCE BETWEEN BEING AN AVOIDE

- Page 27 and 28: No matter how big or small the goal

- Page 29 and 30: ESG RATINGS Schroders has written e

- Page 31 and 32: Advocacy plays an important role an

- Page 34 and 35: WEALTH MANAGER TOP WEALTH MANAGER I

- Page 36 and 37: PORTFOLIO CONSTRUCTION Principles,

- Page 38 and 39: FUND MANAGEMENT Specialists win Gol

- Page 40 and 41: RESPONSIBLE INVESTMENT A FIRST FOR

- Page 42 and 43: What if we considered technology as

- Page 44 and 45: Snakes and ladders The industry tec

- Page 46 and 47: RETIREMENT WHAT THE NEW TAX LAWS ME

- Page 48 and 49: RETIREMENT How an increasing life e

- Page 50 and 51: LIVING ANNUITIES The artificial lin

- Page 52 and 53: FINANCIAL PLANNING It’s Not About

- Page 54: EDUCATION Forging financial futures

- Page 57 and 58: FINANCIAL PLANNING Gaining momentum

- Page 59 and 60: WANT TO RUN YOUR OWN IFA PRACTICE W

- Page 61 and 62: CLIENT EXPERIENCE When you attract

- Page 63 and 64: BEHAVIOURAL ADVICE My career has be

- Page 65 and 66: FOREIGN EXCHANGE • Variable sprea

- Page 67 and 68: Humans Under Management South Afric

- Page 69 and 70: There is an expectation that a blac

- Page 71 and 72: The destination Winning the competi

- Page 73 and 74:

You played rugby for Ireland A befo

- Page 75 and 76:

There can be only one winner in mos

- Page 77 and 78:

THEMATIC INVESTING Discovery Invest

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...